Postcard from the Lodz Ghetto, Poland, 1940.

(Renamed Litzmannstadt by the Germans).

From left to right: Mordechai Feigenbaum

(Avrum's brother), Minka Feigenbaum

(Modechai's wife), and Avrum Feigenbaum.

Courtesy of Avrum Feigenbaum.

|

I was born in 1919 and grew up in Lodz, Poland. From the age of eleven I was an activist in Jewish cultural and political life in Poland in an organization called the Jewish Labour Bund. My upbringing, both inside and outside the home, was politically and culturally Bundist.

I was in Lodz when, in 1939, the Germans occupied Poland. In May 1940, along with my sister and brothers and my parents, I was sent to live in the Jewish ghetto in Lodz. All the Jewish groups in Poland which had been active earlier continued to exist during the war. While in Lodz ghetto, I too remained a member of the Bund.

I worked in a factory as a cabinet maker in the ghetto. The ghetto was completely cut off from the world around us. The most important thing the Bund did was to bring news from the outside world by means of illegal radios that were operated in the ghetto. I was active in my organization, but essentially the same activities were going on in all the other organizations, especially youth groups like my own.

I was in the Lodz ghetto until September 1944. At that time, the ghetto was finally liquidated and the Jews were sent to Auschwitz. We had heard about gas chambers and crematoria before we got to Auschwitz, but it was upon our arrival there that we were confronted with their reality. I was in Auschwitz for five weeks. Some Jews were sent to work in various other camps. I was transported to a camp called Gorlitz, a part of Gross-Rosen camp. There I worked in a factory producing armoured vehicles for the Germans. On 9 May 1945, the day after the war officially ended in Europe, we walked through the gates of the camp.

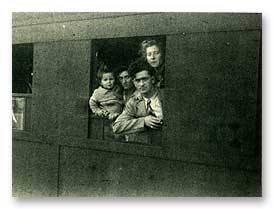

Photograph taken in the Lodz Ghetto by

Mendel Grossman who kept a secret

photographic record of ghetto life. The man

on the upper left is Avrum Feigenbaum.

Photograph published in With a Camera in

the Ghetto by Mendel Grossman (Ghetto

Fighter's House / Hakibbutz Hameuchad

Publishing House, 1970).

|

By June 1945 I was back in Poland. I soon became active again in Jewish cultural and political life. We tried to rebuild, on a smaller scale, Jewish life in Poland, by establishing Jewish theatres, choirs, orchestras, sports organizations, schools and co-operatives. But under the communist regime this was not possible. In 1948, all political parties other than the communist party were suppressed, and, not willing to join the United Communist Movement, I had no choice but to leave my homeland. I went to Germany illegally with the help of the Jewish Labour Committee in New York. The same organization also arranged for me and my wife, whom I had married in April 1946 in Lodz, to emigrate and stay for almost one year in Sweden. As well, they also arranged for me a special permit to enter Canada as a political refugee from Poland. We came to Montreal in June 1950 and have lived here ever since.

The foregoing summarizes the main features of my experiences. What I really want to do here is to express some sense of what it is like to be a survivor of the Holocaust, to try to convey the pain that is so much a part of our thoughts.

I remember when I was in Auschwitz. As I noted earlier, we saw the crematoria and were told, “You see those chimneys? That is Jewish smoke coming out. This is what you came here for. You did not come here to live, you came here to die, and you will. If it is not tomorrow, it will be the day after. You are not here to survive, you are here to die.” And we believed it when we saw what happened there. Yes, we believed it.

In Auschwitz we asked ourselves questions: Did the outside world know what was happening in Auschwitz? Was it possible that the world did not know that people were being systematically exterminated? Today, in hindsight, we know that the outside world did have knowledge of the widespread organized slaughter of the Jews, and that by the time I arrived in Auschwitz what was taking place there was known in considerable detail.

Copy of "Schindler's List" (dated

18 April 1945) listing the names of

780 men and 240 women that

Oskar Schindler saved.

Courtesy of Stefan Lesniak

|

Auschwitz was really an immense series of camps and I was in the part known as the Zigeunerlager, or Gypsy camp. The name derived from the fact that earlier, before they were gassed, the previous inmates of this section had been Gypsies. One of the crematoria was destroyed with the help of four Jewish girls, who, as prisoners working in the nearby German chemical factory IG Farben, which was part of the Auschwitz complex, stole the explosives used to blow up the crematorium. These unarmed prisoners succeeded in destroying at least one crematorium on their own, but the free world, with its armies of millions of soldiers, was unable to destroy anything. We, the prisoners of Auschwitz, wondered at the time: Is it possible that no one cares about us? Are we really forgotten by God and our fellow men?

On 12 May 1943, an event took place in London which attempted to focus attention on the plight of the Jews. Two Jews, Ignacy Schwarzbart and Arthur Zygelboym, were members of the Polish National Council in London. After desperate but futile efforts to get the British government to act to save the Jews, Zygelboym committed suicide. In a farewell letter, Zygelboym wrote: “I cannot be silent. I cannot live while the remnants of the Jewish population of Poland, of whom I am a representative, are perishing... By my death I wish to make my final protest against the passivity with which the world is looking on and permitting the extermination of the Jewish people.”

This is how Zygelboym died. He died, giving his life voluntarily, hoping to shake the conscience of the free world. But the conscience of the world was not shaken.

A similar reaction of indifference to information about the murder of the Jews had occurred in February 1943. A German embassy official in Switzerland sent reports to the American embassy, reports which the Americans were not interested in receiving. In response to a final telegram the state department ordered, “Do not use our diplomatic telegraph anymore for personal information.” Thus, reports about what was happening to the Jews were seen as being merely “personal information”. The Jews were not important, they were not part of the war effort, they were not recognized as a people. (Only the Germans identified the Jews as a people, a people to be annihilated.)

When the nations of the world finally did get together and held a conference on refugees in Bermuda in April 1943, Jews were not officially represented at the conference. There was a Jew, an American congressman named Bloom at the conference, but this was a coincidence. He just happened to be Jewish. He did not represent the Jews as a group. The upshot of this Bermuda Conference was that nothing constructive was done to rescue the Jews. In fact, the reason that a resolution to demand that Hitler permit the Jews to leave Europe was never ratified was not the fear that Hitler would refuse this demand, but that he might actually agree to it. The world was not ready or willing to take the Jews. That was the bottom line.

A Jewish family--Wille and Eva Sterner on the right--aboard a train in Austria, 1948, as they begin

their voyage to Canada. Courtesy, Willie Sterner.

|

My main topic here is “liberation.” I have waited until the end to discuss this because for many readers my thoughts on this may be difficult to understand. Like the pain we survivors felt at the time as well as after the war, when we discovered that the world was unwilling to attempt to deliver us from the Nazis, this word “liberation” is a word that for us is filled with anguish. It is simply because we were not liberated. We just happened to be there when the allied armies had made their way to the camps. This had nothing to do with Jews as Jews. I was not liberated on 27 January 1945 when Auschwitz was liberated. I was not liberated on 9 May 1945 when I left Gorlitz camp. I was not free. We survivors have no nights in which we feel liberated. However difficult it may be for young people reading this to understand, I must say that, literally, our nights are still spent in the ghettos and in Auschwitz. We play the happy people, it is a role we play. We live happily. I live with my family during the day and in Auschwitz at night, and this is why I cannot use the word liberation.

Others might use it. They shared a victory. They celebrated a liberation. Jews have no victory. We were physically destroyed, including so-called survivors. Most emerged at the end with no one, no friends, family, loved ones, parents, children, brothers, sisters. Jews had to start living again, to build from scratch. We tried. We went to Poland, back to our homes. But it did not work out. We could not forget that in the moment when the tormented Jewish people of Europe were bleeding to death, children, the noblest sons and daughters, were butchered daily. We stretched out our hands for help in those days in the name of humanity, not in the name of Judaism, but in the name of humanity. We felt then and we feel today that we had the right to speak in the name of humanity, with our hope, to reach to the end of that darkness in that long night in May 1945.

The light went on, yes it did, for the victorious armies of the allies. The light of victory did not bring us happiness. We will never have true happiness. I am not a young man. I feel almost at the edge of my grave. If I have not yet felt the happiness of liberation, do not feel it now, I, and others like me, will never feel it.

Not only a people, but a civilization was destroyed by the Germans. Jews were the main victims, physically. But we did have one victory over Hitler. The Germans tried deliberately to dehumanize us. In the end, this plan of Hitler did not work on us--it worked on his people, but not on us. I am proud to say we came out from ghettos and camps, not as a liberated people, but as a proud people with dignity. We were not dehumanized. We retained our humanity and today we remind the world that tomorrow it can happen again. If not to the Jews, to others. Other groups might find themselves in a situation where a new Holocaust could happen to them.

Today we often hear people speak of the need for love between the nations of the world. This, of course, is a good thing. But for me, given my experience of the Holocaust, I would settle for something less than love if love is too much to demand of the world. I would settle for learning simply to live together, for simple tolerance. We, all of us, have one world together and this is the world that we have to watch and care for and build every day of our lives. It is possible that some young person reading this today might be a future Prime Minister of Canada or might be a leader in some other capacity. I hope that that person’s generation will produce better leaders than my generation did. So we rely on you, on the new generation, to create a better world than the one we had in our time.

Copyright 1999 Avrum Feigenbaum. From

So Others Will Remember: Holocaust History and Survivor Testimony, edited by Ronald Headland.

JEWISH WAR ORPHANS

Children leave a transit centre enroute

to Kloster Indersdorf Children's Centre,

May 1946. United Nations Archives.

|

Open Your Hearts: The Story of Jewish War Orphans in Canada, by Fraidie Martz, tells the story of the 1,123 Jewish war orphans, children who had survived the Holocaust in hiding or in concentration camps, which the Canadain government reluctantly allowed into Canada from 1947 to 1949 under the terms of a unique federal order-in-council.

This was not only the beginning point of their new lives, but also the culmination of years of work by Canadians across the country. No one knew, given the terrible traumas these young people had endured, what to expect; no one knew the extend of the kindness and generosity which awaited them in Canada.

Drawing on archival materials, memoirs, diaries, and interviews, the author recounts what happened as the European orphans and their new country adapted to each other. Open Your Hearts is first and foremost a human interest story about how children and adolescents, traumatized by the Holocaust and deprived of everything considered essential for normal development, flourished and became productive citizens in the care of a protective community. It also chronicles a unique experiment in the integration of refugees by an ethnic community, an experiment which may hold lessons for current immigration policy in Canada.

Saul Hayes at his desk at the

Canadian Jewish Congress office, Montreal, mid 1940's.

Canadian Jewish Congress

National Archives.

|

Congress Bulletin, September 1947.

Canadian Jewish Congress

National Archives.

|

Group of war orphans at baseball game, Winnipeg, spring or summer, 1949. Photo by Portigal & Wardle. Canadian Jewish Congress National Archives.

|

Books featured on this page:

Open Your Hearts: The Story of Jewish War Orphans in Canada by Fraidie Martz

Winner, 1997 Joseph and Faye Tannenbaum Award for Canadian Jewish History

So Others Will Remember: Holocaust History and Survivor Testimony edited by Ronald Headland.