|

|

|

Oscar Peterson

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oscar Peterson was seventeen years old when he joined the Johnny Holmes Orchestra in 1942. The war was swallowing up young men, and Holmes had lost two pianists in quick succession to the army, just as his band was beginning to take off at Victoria Hall. Holmes was still casting around for a new pianist when saxophonist Art Morrow showed up at rehearsal one evening with a nervous black teenager in tow.Young Peterson didn't have any experience working in a big band, though he'd been playing in a student dance band at his high school. Eager to impress Holmes, he unloaded every musical idea and cliché he knew in to the first tune the band asked him to play. |

|

|

|

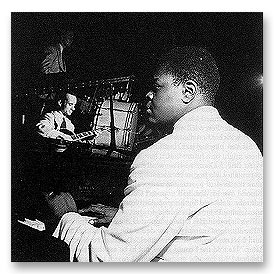

Johnny Holmes and Oscar Peterson during one of their regular meetings at Holmes' apartment, 1944. Johnny Holmes Collection, Concordia University Archives. |

|

|

|

Holmes wasn't impressed; but as the rehearsal ground on, the bandleader began to see a glimmer of hope in the teenager's hyper-exuberant playing. "He was a diamond in the rough," Holmes recalled some thirty years later from retirement. "He already had amazing technique, but he shot everything in the first chorus."

With Morrow's encouragement, Holmes took Peterson aside during a break in the rehearsal and tried to explain to him what was required of big-band pianist. He asked Peterson if he had ever listened to Tommy Dorsey's band. When the teenager said he had, Holmes advised him to try playing like Dorsey's pianist, Joe Bushkin.

At the end of the rehearsal, Holmes hired Peterson, then went one step further. He fixed a date with the pianist for a private get-together, to go over the band's music. The meetings became more regular as a friendship developed. Over the next two years Holmes and Peterson met several times a week, for up to two hours at a time. Holmes played only rudimentary piano, and there was nothing he could show Peterson about keyboard technique. He did, however, coach the young pianist on jazz conception and delivery, playing records to illustrate fine points of phrasing and performance. The influence on Peterson's playing was profound. "I was overdoing boogie-woogie and was completely lost for slow tunes," Peterson told a magazine in 1946, after making his first recordings. "Holmes was responsible for changing this; he built up my technique and was responsible for the style I put on records." |

|

|

| Peterson blossomed with the band. As time passed, Holmes recognized that his pianist was a major contributor to the band's success and popularity. He acknowledged Peterson's drawing power by paying him more than any other band member; eventually Peterson was earning a living from the band, the only member besides Holmes to do so. Holmes also began including Peterson's name on the band's publicity flyers and newspaper ads, billing the band as "the Johnny Holmes Orchestra with Oscar Peterson." He gave Peterson liberal solo space in his arrangements; a popular ballad called "Dark Eyes" became Peterson's feature number. Finally, Holmes began turning the last fifteen minutes of every dance over to Peterson and the band's bassist and drummer, giving the pianist the first taste of the trio format that was to become the staple of his career. Recalled Holmes: "The last fifteen minutes we played |

|

|

|

|

Oscar Peterson on stage at Victoria Hall with the Johnny Holmes Orchestra. In the background are drummer Russ Dufort and guitarist Armand Samson. Johnny Holmes Collection, Concordia University Archives. |

|

|

|

all the slow and dreamy music so the kids could dance very close together. We just let Oscar play. He'd call the tunes…But he'd be playing, say, 'Body and Soul,' and someone in the band would call out another tune, say 'I Surrender Dear.' And he'd have to incorporate that right away into 'Body and Soul,' whether it was on the third beat of the bar or whatever. He never got hung up once. And they were calling out ridiculous things, classicals, everything. He would never get hung up at all… The band idolized him. The greatest audience he had was the band."

One day during the winter of 1944-45, Peterson told his mother he'd like to make a record. She suggested he telephone one of the record companies and tell them what he'd just told her. He called Hugh Joseph, the man in charge of RCA Victor in Canada. By coincidence, Joseph himself had been considering calling Peterson, whose reputation had reached him. With a firm offer of a recording contract from Victor, Peterson turned to Holmes for advice. The bandleader effectively became Peterson's manager for his first recording contract and session. Though Peterson insisted on writing a twenty percent commission for Holmes into the contract with Victor, the bandleader never collected on it.

|

|

|

|

An excerpt from Swinging in Paradise: History of Jazz in Montreal. Copyright 1988, 1989,

John Gilmore.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|