|

The Avi Boxer Archives

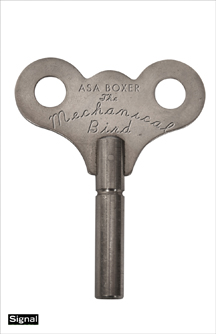

Snap-Shots and Recollections Asa Boxer

Avi Boxer was a Montreal East-end poet who flourished during the 1950’s literary foment alongside A.M. Klein, F.R. Scott, Louis Dudek, Irving Layton and Leonard Cohen. Opening my cabin in Val Morin after a nine-year stay in Israel, the usual cold mustiness met my senses, but this time the feel had something of the crypt to it. Of course, standing under the cathedral ceiling, memories of my late father have a way of hovering, probably because he built the place, but there was something more. In the attic, unseen, unthought of, fifteen boxes of his books silently awaited their disturbance, while photographs holding quiet evidence of drunken poets and general debauchery were patiently nestling in a box among some linens. Michael Harris, mentor and old friend, now a book dealer and collector, encouraged me to go through the books in search of hidden treasure—books that had not been set aside with my father’s collectibles, having had no value twenty years ago, but now possibly

I also excavated a box of numbered and signed copies of my father’s book No Address; alongside No Address manuscripts, book and cover-design work, and proofs. Always a self-advertised Virgo, he was meticulous with everything (which meant that the line between getting involved and taking over was often crossed); he tailored every aspect of his book to his taste, making it an artifact of his intellect, his will, his heart, and his idiosyncrasies. Even the DC logo, as it appears in his book, is his. The back flap says it all: “COVER CONCEPT, GRAPHICS & BOOK DESIGN by Avi Boxer.”

No Address expresses this sense of discipline in several ways. For instance, the first poem pictures a chrysanthemum on black hair, and the last piece, in haiku form, echoes with an “orange bow” on a “long black braid”—a “touch” he was proud of. The front flap, with its short bio is another example of the Avi Boxer “touch.” If Jan Clark (the purported writer of this bio) ever existed, then most of what ended up in print was not hers; the wit, the humour, and the turn of phrase are his own. Most importantly though, was the image he was projecting. His sensitive mystique comes first: “Avi Boxer, Montreal 1932, once told me he began writing poetry when he bought his first pencil from a blindman’s cup. I tend to believe him.” His working-class origins come next, then his stint as “advertising manager, and creative director for an ad-agency,” followed by his beatnik turn in 1960, his work as a ghost-writer of two Master’s theses (in Sociology and English Lit.). Some emphasis is placed on the ironic fact that he “simultaneously received a ‘C’ grade in English Composition and the Board of Governors Gold Medal for Creative Expression.” The bio closes with a word about his work on educational films in New York, his nomination to the League of Canadian Poets, and the time he “now devotes” to “his Laurentian country estate and his ‘original hate,’ poetry.” Career oriented as the bio is, there are intimations of honest sensitivity, dynamic energy, a sense of irony, and something darker than irony in the ghost-writing. The cover presents a similar picture, a charcoal textured beatnik on the roadside, the ghosts of his parents looming larger than life between background and foreground, No Address stamped in red diagonally across the black and white. This was the carefully styled self-image of a one-time ad-agency creative director who had worked on campaigns for companies as big as Texaco and Pepsico, now holding “a BA with joint-majors in Sociology and Psychology.” Controlling one’s image inevitably entails some elision and a few dabs of cover-up, but we will come to this in a moment.

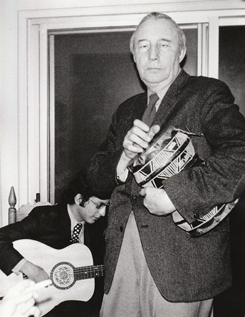

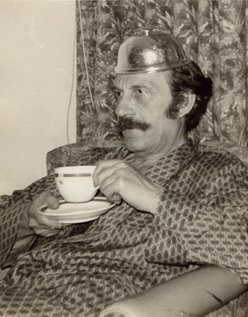

Poking around back in the attic in Val Morin, I came across a batch of photos I had been looking for; this is a collection of candid photos of a whole slew of Canadian poets. My father had (apparently) tried to sell the photo-collection to McGill only to have it turned down because the shots were candid! I brought them over to Michael Harris’s and we spent an enjoyable couple of hours going through this wonderful cultural archive and, wherever possible, indicating names and dates. Priceless in my eyes are images of Frank Scott on the bongos; Louis Dudek on the accordion; John Richmond as “Don Quixote in Housecoat,” slumped in an armchair with a cup of tea and a silver platter-cover on his head; Margaret Atwood, happily sandwiched between Purdy and Boxer with an inscrutable but definite look of meaning in the sideways and upward glance and smile she is pouring over Al Purdy.

A photograph of Betty Layton, her elbow resting on my father’s shoulder, was taken in 1955. Michael pointed out the pictures of Irving Layton’s kids top centre of the cropped photograph. As I heard the tale, Avi and Betty ran off to San Francisco together in 1960 (which helps explain the provenance of my solid Layton collection in multiple copies and editions). The No Address flap elides this uncomfortable elopement with an evasive joke: “In 1960 he left for North Beach, San Francisco, to review Sartre and question the Beat Generation.” His involvement with witchcraft and black magic in a New York coven is similarly covered over with the following phrase: “Sidetracking from his PhD in New York . . ..”

I was five years old. It was a stormy night. My father called me into the master bedroom. The lights were dim and he held a dim lamp under his face. He spoke with a strange voice and insisted that he was not my daddy, but his evil twin. Sometimes Avi Boxer’s doppelganger was playful, but, at times, the “games,” as he called them, had exacting consequences. Toward the end of his short life, the centre of gravity shifted and things spun out of control: one of his close friends went insane, another committed suicide. And then, of course, there was his death, leaving my mother and I to battle each other in court, my father having stipulated in his will that I be placed in the care of a foster family—a state of affairs that my mother, for obvious reasons, could not accept. After a force like that bears down hard on your life, black magic seems plausible enough.

Return to Véhicule Press |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||